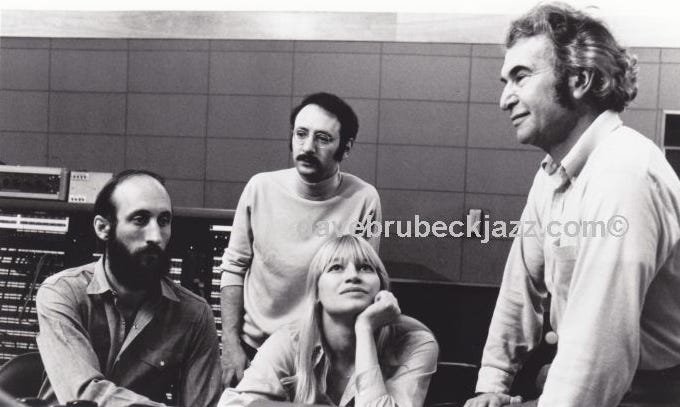

Noel, Peter, Mary, and Dave Brubeck listen to the playback of their recording session at the Columbia Studios - photo courtesy DAVEBRUBECKJAZZ.COM

If you’ve heard some of the songs on Noel’s latest album Fazz:Now & Then, you know that Noel loves jazz. In fact, the album’s title came from a moment when Peter, Paul, and Mary were touring with the Dave Brubeck Quartet. Saxophonist Paul Desmond invited the trio onstage for the song “Because All Men Are Brothers” and suggested to the audience that the resultant music created by the seven of them might be called “jolk” or “fazz.”

When I learned that Bill Carter’s Thriving on a Riff: Jazz and the Spiritual Life was released just last month by Broadleaf (He’s William G. on the cover), I could not wait to read it. By the end of the first chapter, I knew that it was all I’d hoped it to be and more.

Author Bill Carter is the jazz pianist and leader of Presbybop jazz ensemble as well as and pastor of First Presbyterian Church of Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania. Having integrated his two vocations for over thirty years has well prepared him to write a book that connects jazz history and theory with spirituality and theology in creative, surprising ways.

I was especially moved by the story of Dave Brubeck’s 1958 concert at Eastern Carolina where the dean of student affairs refused to let the band play because the it included a black bass player. Brubeck argued, “Tomorrow I’m taking my band to play behind the Iron Curtain, and you’re telling us that we can’t play in our own country.” It took a call from the college president to the governor of North Carolina to turn the no into a go.

Certainly, Noel and the trio had their share of ethical challenges as well. Not withstanding the early blacklisting of their records in the deep south following their appearance at the March on Washington in 1963, they had also faced the animosity of segregationists earlier in their performing career, travelling with the Javanese bassist, Eddie de Haas, whose list of credits had included such jazz greats as Terry Gibbs, Miles Davis (1957), Bernard Peiffer, Sal Salvador, Benny Goodman, Charlie Mariano/Toshiko Akiyoshi, Blossom Dearie, Charlie Singleton, Chris Connor, Kenny Burrell, Roy Haynes and Kai Winding (1958/59).

But this particular Substack post is less about overcoming external injustices and more about how the medium of jazz encourages the triumph of imagination over internal stagnation and encourages the evolution of the creative force in each of us. In his book, Carter seamlessly connects both jazz and spirituality with risk, freedom, and joy. He writes, “The act of playing jazz—like daily life, like the spiritual life—is an informed risk. Improvisation happens through nimble fingers, serious training in music theory and form, and a willingness to jump into uncharted territory.” And in a sermon, Carter speaks of the intersection of spirit, worship, and jazz:

What I have learned about jazz in the church is that people really want it. Even if they sit scowling with their arms crossed, they really want it. They want to be in the presence of the energy and imagination. They want the passion to kiss them alive. They want their own frozen hearts to defrost. And it’s not the jazz per se; it is what’s behind the jazz. They want to know there is a deep joy at the center of the universe that has the power to make all things well.

Every singer/songwriter shares a willingness to explore the unknown during the creation of a new piece. And it is in the trusting of that process that the most memorable compositions are produced and become part of what is ultimately considered timeless—folk music. Some musicologists, in their well-intentioned attempts to categorize musical styles are often at loose ends trying to pigeon hole just what constitutes folk music. “It’s traditional”, they maintain. And yet, so much of what has become part of our world’s musical legacy had its contemporary moment before transcending time itself. Or in the oft-quoted words of Louis Armstrong, “Hey man…everything is folk music! You never heard a horse sing, did ya?!”

Carter helpfully includes a glossary of terms in his book with definitions that have more personality than the ones you’ll find in a dictionary. To wit, he explains that jazz “has often been described as a musical style, a category for selling recordings, or suspicious cacophony that frightens church organists and enervates symphony violinists.” But he clearly prefers this one: “Jazz describes music that blurs any distinction between composition and improvisation.”

One and the same … and truly, any kind of creative effort can be viewed as an “offering” of sorts. A song, a poem, an idea of how to reconfigure an apartment, an inventive deviation from the usual car route home. A trust that an unknown quantity of life is part of life itself. Carter says, “When imagination is suppressed, when order is imposed, when the jazz factor of God’s creation is denied, the human need for control becomes addictive--and has led to some of the grimmest chapters in human history.”

Jazz was quite popular in Germany before Hitler came to power, but the Third Reich banned it because it was “too spontaneous, too unpredictable, too free.” Hitler called for marches instead. Artists and musicians who crossed the boundaries landed in jail and concentration camps. Carter writes: “History shows us this is what repressive governments do. They impose order in their people and predictability in their God. The issue is freedom. At such points in history, the music is codified, and the church is controlled, God is not free. Neither is anybody else. Creativity can be a threat to those who wish to maintain control.”

The title of Carter’s book has a meaning beyond its musical one. “Thriving on a riff” suggests to me that thriving depends on creativity. A flourishing and just world depends on imagination and improvisation. Creativity matters not only in the arts, but in every realm of life—education, health care, governance, human services, and care of God’s earth.

Several weeks ago in a previous Substack, we introduced the concept of an open and relational theology—complete with its affirmation that creation is ongoing. But surely in the process, we need an anchor… some kind of redemptive base that we can trust. so the question becomes, what is the overarching principle that would allow—even encourages—the taking of those chances? Could it be something as simple, as profound, as deep as Love?

Connections

Here is Bill Carter introducing Thriving on a Riff.

Read this short meditation “The Jazz Gospel” from the Center for Action and Contemplation.

Hear and watch the story behind the Vince Giraldi Mass.

Vibrations

The Dave Brubeck Quartet and PP&M perform “Because All Men Are Brothers.”

Watch and listen to Noel’s scat singing in his song “The Lady Says.”

Resonance

If you were to have a conversation with God (a process <grin> often called prayer), would you refer to some written notes you had assembled or rather speak from the heart? Which form do you think God might prefer?

What was your first impression of jazz in a worship service? If your appreciation of that combination has grown, how did that change happen?

depending if a person looks on the world in ahhh and wonderment in the tiniest dandelions or if a person would look for dust on the bend of a frame housing one of the most beautiful painting known to man. This might be very naive of me,but I can't think of anything that could not be used by God . I helped start a alternative high school . We had to abide by Pa.state's rules of course especially to graduate ! I chose to write an essay on how you can use math when trying to choreograph a dance.( I detest math). Even as how the numbers are ,start by placing your dancers along the numbers themselves for a start,begin combinations,etc. Believe it or not they accepted it for my math portion ...the same can be used for jazz.it's what the musician brings to the playing,the piece etc.

My appreciation of jazz as prayer has grown and prompts me to speak extemporaneously with the Divine. I think of two OT myths/metaphors. The discordance of sound from the Tower of Babel has become intelligible diversity. And the dry bones from Ezekiel can reform and animate. These demonstrate the power of Easter to reconcile and renew "the old or off-center notes." .... Since the Big Bang, the Universe seems to arrange chaos into order like jazz instruments eventually finding the same note, whether you call it Om or Logos. When I look at the varied structure of galaxies, I think that God must be doing scat. Jazz improvisation, different forms of prayer, the variety in nature--all are great examples of nonduality. The riffs are complementary, not contradictory.