The Authenticity of Intent

Keynote Address at Folk Alliance International Conference

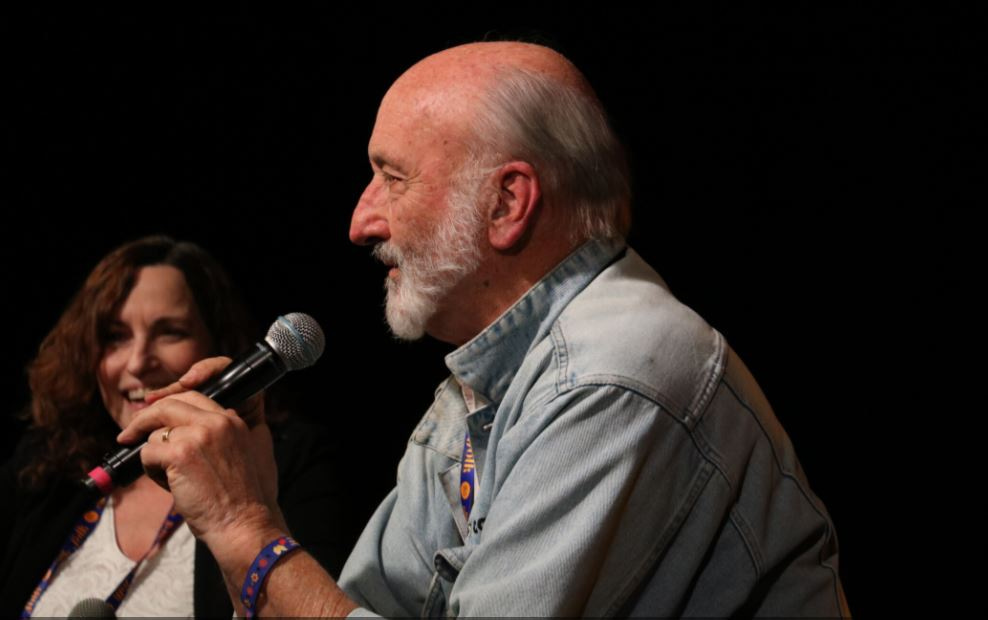

Deana McCloud (FAI moderator) and Noel Paul Stookey (keynote); photo by Nick Spacek

I recently accepted an invitation to deliver the keynote address at the 2024 Folk Alliance International Conference in Kansas City, an event that draws three to five thousand folk musicans annually. I had the feeling that over the next four days many of the attendees would be looking at their work in the light of its relevance to contemporary times in much the same way that Peter, Mary and I had in the early 60's.

The participants come from all over the world and from a wide variety of musical disciplines: country-western, indigenous Lakota, pop-rock, jazz and blues, gospel and children's music. To be asked to address such a vibrant and contemporary community was an honor that caused me to recall that in the early days of our 50-year-long career the trio's repertoire had been dismissed by some critics as too “slick,” too modern to be considered folk music.

I remembered the how, when, and why that trajectory of acceptance was changed for PP&M. We didn't attempt to emulate the folk music styles or performance characteristics of the earlier decades, nor did we—and I think this is more to the heart of the issue—believe that what we were doing on stage was simply entertainment.

Over the years, the songs we wrote and/or chose to include our performances began more and more to echo the concerns of the times in which we were living. The Civil Rights movement of 1963 became the parent—the progenitor—of a realization that any injustice was a ultimately a violation of human rights, whether its form was legal, political, social, financial or even ecological.

Borrowing songs from Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Pete Seeger and the Weavers and the more contemporary works of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver, we began a journey of musical conscience that had perhaps its first most public voicing at the March on Washington in 1963 and continued well into the 2000s, taking us to communities as diverse as the vineyards of California, the campus of Kent State, and the countries of the Phillipines, El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Of course, in those instances, music was the important emotional and often hopeful thread connecting both the performer and the listener to the reality of an issue. But perhaps even more importantly, a kinship was developed with our audiences— particularly with those dispossessed and disenfranchised—those who recognized a common authenticity of intent.

It was that phrase, the “authenticity of intent” that then became the cornerstone of my talk at FAI. I suggested that a song's genre mattered less than an honest and revealing focus on the part of the singer/songwriter. And by virtue of the inclusiveness of that perspective, I was able to salute and encourage the individual FAI attendees regardless of their performing style.

I confessed my slow awareness of modern rap music, but by linking the early days of its development to the expression of frustration and anger at the inequities experienced by black communities, I pressed the point of how the “authentic intent” had created both the content and the urgency of the genre.

Reflecting on how the expansion of that concept was a parallel of sorts to much of my songwriting and spiritual life—a metaphorical expression of faith rather than the reliance on doctrinal terms—I understand now why the final moments of the keynote then became so special.

When the moderator suggested I finish my talk with a song, I said I would volunteer a note. That is, I would start with a single tone and invite the 200 or so folks in the room to join me by adding their individual harmonies. In essence, I was asking them to lay aside their mandolins, their guitars, banjos or fiddles and just use the one instrument we all had in common: our voices. There would be no words, no familiar melody...We would see where it would lead.

For almost two minutes, the room was filled with a rich, enveloping, wave of what seemed like angelic voices, affirming the value of each others company and something else: something unnamed. The experience became holy. It was an amen acknowledging a sensitive wordless moment from a sea of hearts immersed in an authenticity of intent.

Connections:

Note from Jeanne: It was a delight to read Nick Spacek's appreciative comment about Noel's address in KC Pitch, a local newspaper:

Getting to hear Noel Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul, & Mary chat with Deana McCloud of Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame was something else. He full-on asked questions of McCloud, told stories, and managed to weave together this mystical creation which also felt like the coolest professor I’d ever had combined with your friendliest grandparent. Musical theory–the idea that folk came out of change in the wake of World War II is intriguing–mixed with personal reminiscing and a broad knowledge of pop music made for alchemy in the truest sense. “Authenticity is in the intention,” he said at one point, and I could’ve listened to him speak far past the sadly short half hour.

McCloud suggested that he end their time with a song and, rather than picking up the banjo and dusting off a favorite, he started a vocal tone, invited the audience to join in and extemporize, and there was two minutes of beautiful joy.

Vibrations:

Hear the “wordless moment from a sea of hearts immersed in an authenticity of intent” at the close of Noel’s address at the 2024 Folk Alliance International Conference.

Resonance:

What is your experience of a wordless revelation among a group of people?

I attended the conference, and was very impressed by Noel's message. In light of the socially-conscious message he delivered about how the songs of the 60s had meaning and reflected the concerns of the times, I think it is relevant to point out that during the 20-year period between 2001 and 2021, there were virtually NO anti-war songs played on mainstream radio in this country, at the same time as our troops were enmeshed in two 20-year-old wars. The difference (in my opinion) is that the draft was gone, and these wars were fought by an all-volunteer military. With young Americans not at risk of getting drafted and sent to fight and die, the college campuses were virtually silent about those wars (including the war in Iraq, which the facts later showed was started on false pretenses after stories of nonexistent "weapons' of mass destruction" were fed to Congress and the American public). I can name a handful of talented, socially-conscious singer/songwriters who wrote some very compelling songs during this period, yet nobody knows their names because Americans (including myself) didn't do a thing to call for these wars to end because it was somebody else (or somebody else's kid) who were fighting and dying in them. Had PP&M come up in, say, 2005, they would (sadly) likely be complete unknowns today.

Beautiful, and thought-provoking, Noel. I agree that "authenticity of intent" is integral to folk music, and to other genres where the songwriter has a message he/she needs to share. As for the one note melody, can I suggest that anyone interested in this listen to what Jacob Collier is doing with his audiences in concert? He brings an energy, a magic and a union with the audience to these concerts that I have not felt since the Peter, Paul and Mary concerts. The audience becomes the instrument. It is "awesome" -- when the word meant something.